Relax, Don’t Stress: Health and Potential of West Hawaiʻi Coral Reefs to Recover

Hawaiʻi’s cherished underwater environment has been wavering between seasons of health and seasons of stress in recent years. Now managers of Hawaiian coral reefs are monitoring vital signs after the NOAA Coral Reef Watch report on the world’s worst coral bleaching and die-off ever recorded, which began in 2014 but is predicted by NOAA scientists to end this year. In particular, the big island of Hawaiʻi is providing crucial evidence of this global phenomenon.

But where are the healthy reefs now in Hawaiʻi, and which reefs have the best chance of staying healthy for years to come, even as waters get warmer and warmer? A new report funded by the NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program (CRCP) shows healthier reefs cluster in the southern portion of the West Hawaiʻi Habitat Focus Area, where intense research is guiding a community living on the edge.

Finding Healthy Reefs in West Hawaiʻi

Hawaiʻi’s coral reefs first began showing signs of stress in 2014, and ocean warming and coral bleaching were observed over broad scales throughout the Islands. In 2015, the bleaching event continued and bleaching intensified due to unusually warm waters caused by a strong, persistent El Niño.

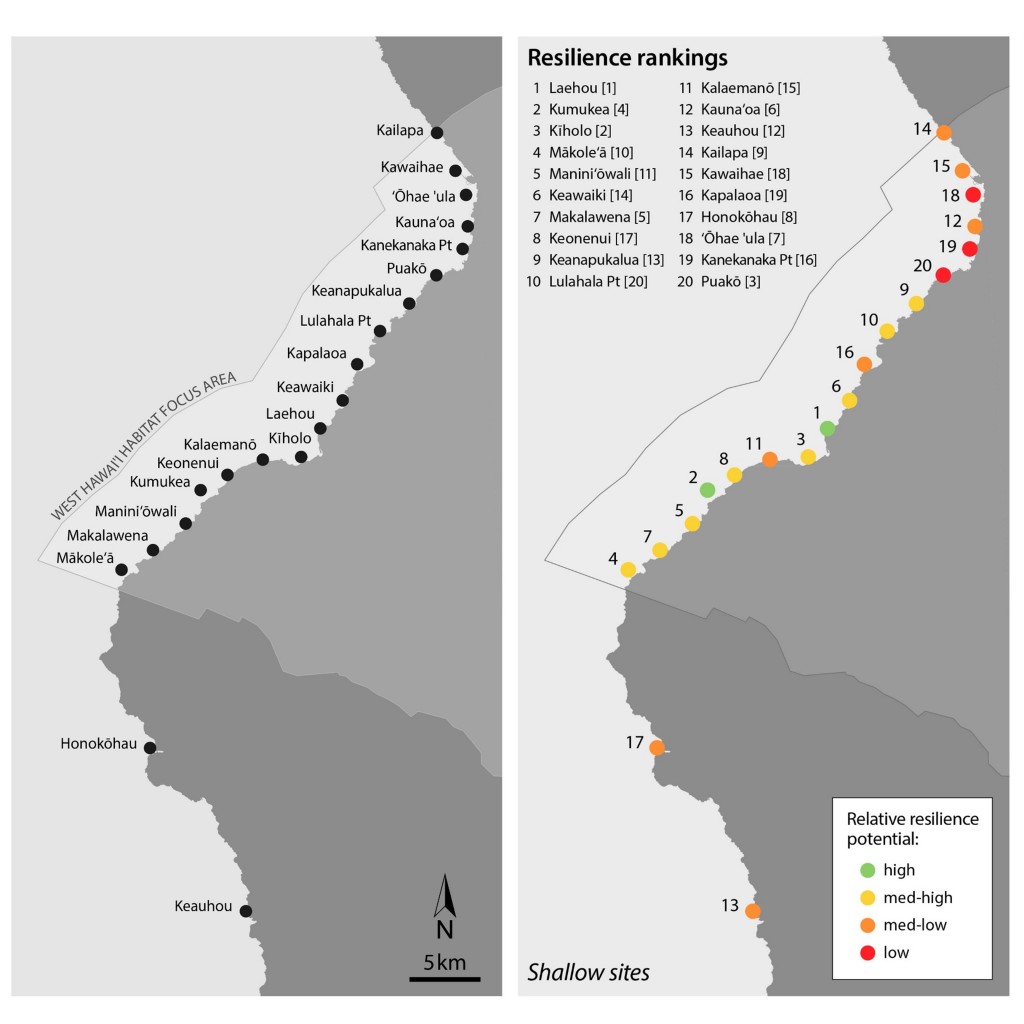

Over the past few years, there has been a collaborative effort between researchers from the Hawaiʻi Division of Aquatic Resources, The Nature Conservancy, NOAA, the University of Hawaiʻi; and community organizations to survey and assess this mass bleaching event, the health of coral reefs and their resilience, and the ability of corals to resist and recover from bleaching. The researchers conducted surveys at 20 different locations near the shoreline of West Hawaiʻi in October 2015, and ranked each site by their health and stress resilience potential.

Left: Map of study sites in South Kohala, West Hawaiʻi where shallow and deep coral reefs were assessed within the NOAA West Hawaiʻi HFA and North Kona.

Right: Coral reef health and resilience rankings for each site. Healthier reefs more resilient to stress were observed in the southern portion of the West Hawaiʻi HFA, while less healthy and resilient reefs occurred further to the north.

Along West Hawaiʻi, the report shows that healthy, resilient coral reef sites had higher resistance to bleaching, greater reproductive success, more herbivorous fish, and less disease than unhealthy reef sites. Monitoring activities will continue through 2017 thanks to additional funding from NOAA CRCP to monitor the resilience of coral reefs to bleaching.

The Value of Healthy Coral Reefs

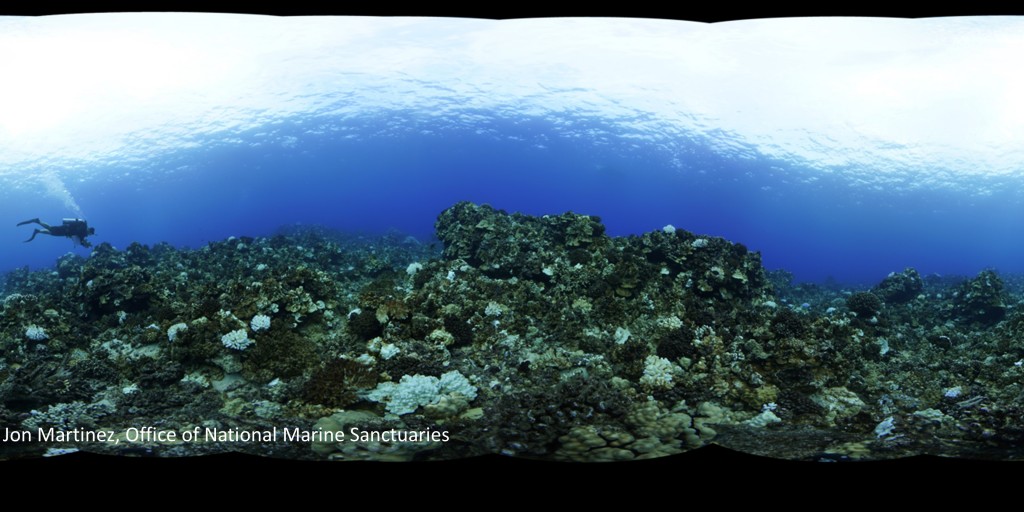

Healthy coral reefs are diverse and valuable ecosystems that support a variety of fishes, corals, crustaceans and other invertebrates. In fact, coral reefs are considered “Essential Fish Habitat” because they are necessary areas for fish and other organisms to reproduce and survive. Healthy reefs also provide numerous benefits to people: they protect our coastlines from waves and storms, and can be the foundation of local economies by supporting fishing and tourism opportunities such as diving and snorkeling tours, hotels, and restaurants. But corals themselves – the building blocks of these vital ecosystems – face threats such as pollution and rising ocean temperatures that cause coral bleaching. These threats can all significantly affect coral reef health.

Bleaching Threatens Reefs Worldwide

Corals have a mutually beneficial relationship with tiny algae that live in their tissues. These algae use sunlight to make their own food and energy, just like other plants. In exchange for a home, the algae shares food and energy with its coral host, helping the coral to survive and grow. The algae are also the source of the many bright colors corals’ have.

However, the tiny algae may abandon coral if either experience high levels of stress, ultimately depriving coral of its primary food source and characteristic color. This process is called coral bleaching (see graphic on coral bleaching below). Bleaching is primarily caused by higher-than-normal ocean temperatures, though pollution and runoff can increase the sensitivity of corals to temperature stress. Bleaching can occur at local, regional, and global scales, and some corals can resist and recover from bleaching better than others.

Alarmingly, in the present report, the researchers found that 68% of West Hawaiʻi’s shallow coral reefs and 60% of its deep reefs were partially or fully bleached in October of 2015. Between 50 and 99% of the corals died due to the bleaching event at some sites surveyed along West Hawaiʻi. Since ocean waters are expected to continue to warm, bleaching events are expected to increase in frequency and severity.

Next Steps

The team is working with partners to determine how human activities may influence the ability of coral reefs to resist and recover from the temperature stress that causes coral bleaching, in both good ways and bad. They are assessing levels of sediment erosion, sewage, land-based fertilizer pollution, coastal development, and commercial and recreational fishing at survey sites to see how these stressors caused by human activities relate to survey results.

The team will then identify potential management actions that may be able to support or improve recovery of unhealthy reefs and maintain the healthier reef sites, and they’ll present these action options to state resource managers. Ultimately, these conservation efforts will help ensure corals on the vital reefs of West Hawaiʻi continue to provide homes for numerous animals, and can be enjoyed by all ocean users.